The Mound - #43 Pop Culture is Dead. And Democracy Killed It.

Welcome to The Mound, a weekly newsletter in which we at Good One Creative pitch— for free — our solutions to the world’s problems.

Another one bites the dust: Byron Bay’s Bluesfest has officially joined the long and growing list of deceased music festivals in Australia.

Yes, it would seem that, due to poor sales, popular culture has been cancelled.

How on earth could this happen? How can popular things die for lack of customers? We might point at COVID or to increased supply chain costs - but the extinction of live music in Australia has been going on for at least ten years now. Let’s not forget that Big Day Out, at one point the biggest touring festival in the world, was cancelled back in 2014 due to poor sales.

If we are to figure this out, we might need to revisit our understanding of popular music and mass markets.

I wasn’t there, of course, but I would have to imagine that the legacy music media brands of the twentieth century (record labels, radio stations, festivals etc.) won the hearts and wallets of their audiences by giving them what they wanted. Their current predicament would thus suggest they no longer understand what people want. They no longer have the goods.

But what if these brands never knew what we wanted? What if we never really wanted what they had? What if popular culture never actually existed?

What we’re exploring here is the possibility that we as individuals are far less to blame for our musical tastes than we think. The term “popular music” itself implies the existence of both a discerning crowd and the agreement amongst them. It suggests that we the people were in fact responsible for elevating certain artists to the top of the pops and consigning others to the waste-bin of oblivion. But if this were exactly true, a music festival boasting a line-up of the most listened-to musicians in history would have no trouble attracting sales.

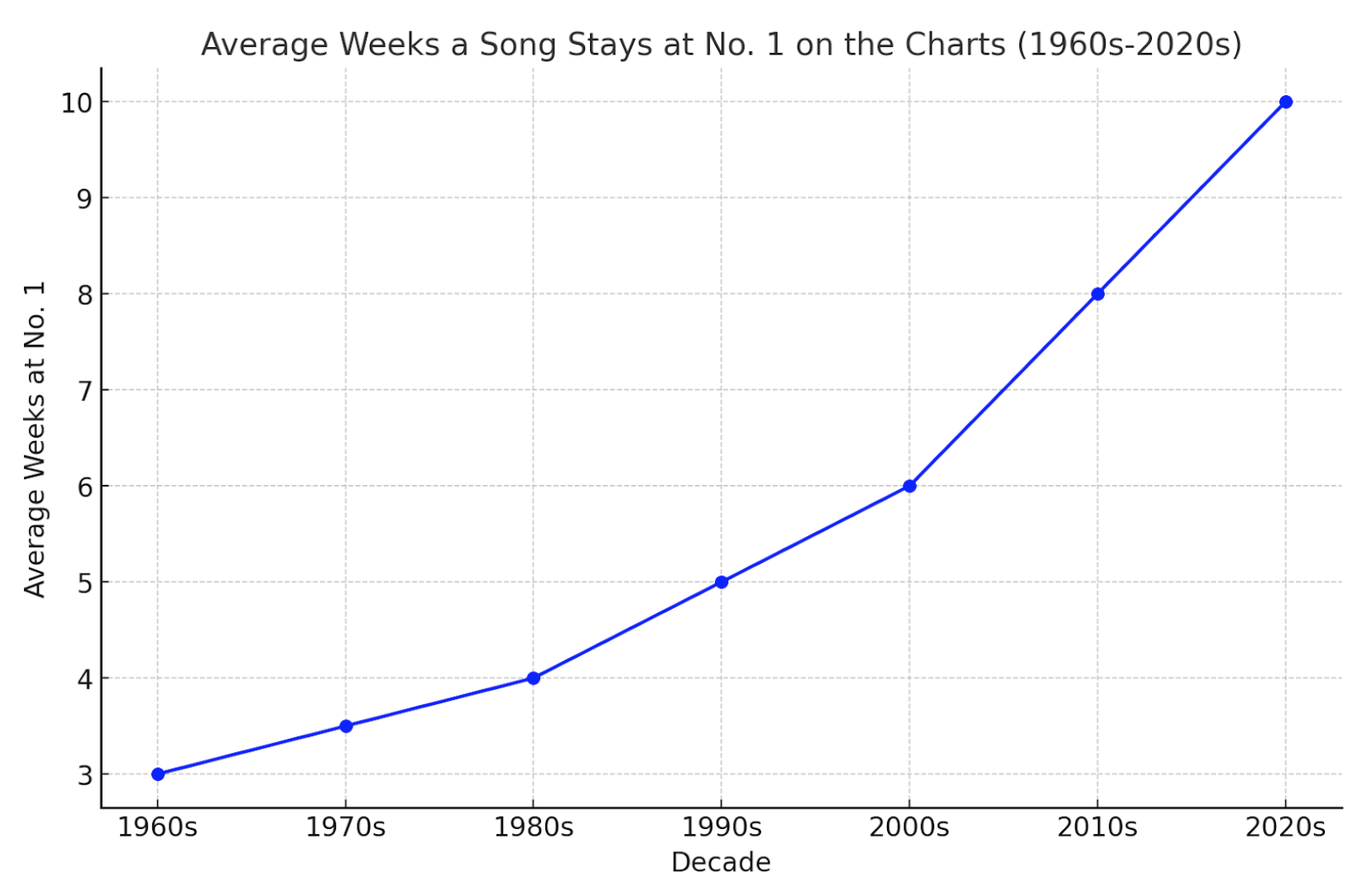

I believe the key to understanding this predicament can be found in the below:

Would you have guessed that? That, for all our talk of cultural acceleration and the ever-shortening trend cycle, things are slowing down?

It wasn’t until a friend (thank you, Baklava Bolshevik) linked me to a recent episode of the Cluster F Theory Podcast that I was able to understand how the above graph could exist. In the episode (which you should listen to) Jason Farago, a cultural critic for The New York Times, discusses the stagnation of culture in the 21st century. He offers several very cogent reasons for the phenomenon: the era’s slow productivity growth, algorithmic consumption patterns, and the bare fact that today’s music has to compete with yesterday’s in a way that it just didn’t during the late twentieth century. The most interesting comment, though, belongs to one of the show’s hosts, Gia Milinovich, when she offhandedly muses that both she and her teenage son listen to the same modern artists. Strange, when you consider no two consecutive generations could have said this in the past.

Hearing this, I returned once more Professors Romaniuk and Sharp’s hugely influential How Brands Grow (2010):

“When a brand is small, more of its customer base is made up of heavy category buyers… If a brand is fortunate enough to grow, then its customer base will change - a greater portion of its customers will be lighter category buyers, and a smaller portion will be heavy category buyers.”

Back in the 1960s, music had a massive distribution issue in that it was relatively difficult to consume. Therefore, the majority of music’s consumption was done by people who had the time, the money, and the passion required to consume it (teens / young adults). And the relatively high cost / difficulty of getting new music meant that, when they found a song, they would have listened to it again and again and again. Compare this to now - in the year of our lord 2024 - when people who don’t even like music are able to put something on in the background at close to zero cost.

The Pareto principle would suggest that today roughly 80% of music consumption is done by a heavy-listening 20% of the population, or “the valuable few” - but Romaniuk and Sharp’s findings suggest that, over time, as much as 60% of a really, really popular song’s downloads/streams/listens actually come from the people we have just described - people who do not care about music, people who use it like air conditioning, people who rely upon the algorithm to play something popular, believing that it is just barely preferable to silence as they tidy their living room or drive around the corner to the shops.

Now that music is pretty much free, pop music is made popular by people who do not listen to music very often. And because they don’t listen to music all that often, it takes them longer to grow weary of certain tracks. The free-availability of music has changed the shape of the market, birthing an average consumption pattern that acts almost like a mud beneath the wheels of culture. Lil X or The Ys can stay at the top of the charts for 15 weeks because the people listening to them aren’t listening, not really.

And that may be our sole consolation: until we can supplant ‘number of listens’ with a more sophisticated combination of evaluative practices (or TASTE, for God’s sake!) we can assuage our distaste for popular music by remembering that no one likes it. Not really.